My introduction to caesarean section was a personal one. It came 8 ½ years ago when my daughter was born that way. Four years later my son was born at home, as planned, after a quick but straightforward labour.

In order to come to terms with my caesarean experience I needed to do a lot of research and reading and soon built up a good library of information. By the time my son arrived I was already sharing this with other mothers, and each one I spoke to added to the depth and breadth of my understanding.

It seems that an increasing number of women these days are asking for an elective caesarean. Provided their choice is based on good information and not an unrealistically rosy impression and that they are making a free personal choice then I believe they should have a right to have that choice respected. These are not the mothers I wish to talk about today. I want to talk to you about the other side of the coin, the mothers who wish to avoid a caesarean, for whom birth is important. They, too, have a right to have their wishes respected.

Although there are no figures I believe that the large majority of women would prefer to avoid an operative delivery of any kind. Most of the mothers I speak to in the course of my voluntary work are what I think of as VBAC Mothers. VBAC is V. B. A. C. and stands for Vaginal Birth After Caesarean. VBAC mothers are women who have had at least one caesarean and who wish to have a VBAC. I think of them as VBAC mothers even though they have not yet achieved a vaginal birth after caesarean.

Most of the published VBAC rates are around 60-80%, some are even higher, however these figures are based on numbers where those deemed 'unsuitable' for VBAC have already been weeded out. It can be much more enlightening to find out how many caesarean mothers booked with a particular hospital go on to have vaginal deliveries. One hospital for instance has a reported VBAC rate of only 11% and a very large proportion of those are delivered by forceps.

This may seem an odd question to ask, particularly when it's a VBAC Mum and one who's had a home delivery who's asking it. However this question, in the form of either an accusation or a threat, is one that VBAC mothers have to face every day.

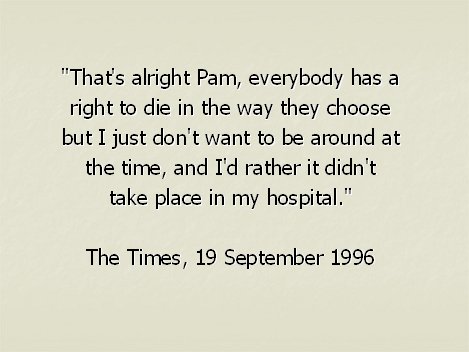

Most often the message is implicit. Conveyed by turn of phrase or tone, but occasionally it is put very bluntly. 'The Times' carried an article recently where this was the response to one mother's request for a VBAC:

"That's alright Pam. Everybody has a right to die in the way they choose but I just don't want to be around at the time, and I'd rather it didn't take place in my hospital"

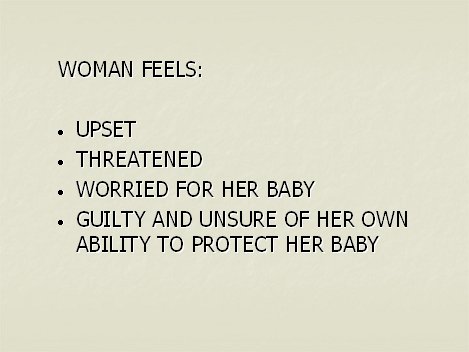

It is very damaging and disempowering to be on the receiving end of such a message. It leaves a woman feeling:

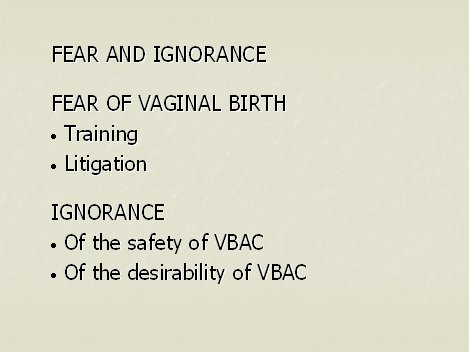

Where do these sorts of messages come from? What is behind them? I can only conclude that it is fear and ignorance.

Firstly fear of vaginal birth. Obstetricians are not trained in midwifery. Their training is concerned with dashing from one interesting complication to the next. They are concerned with the small percentage of women who do have a need for specialist obstetric attention. We cannot, therefore, realistically expect obstetricians to have a balanced view of birth.

Fear of litigation. Obstetricians are worried about litigation. If a baby is born damaged the threat of legal action is there for the whole of an obstetrician's career. All children qualify for legal aid and there are no time limits to bringing a case. If you are the parents of a damaged baby you feel a duty to that child to take action. All parents want the best for their children.

Hospital complaints are often even more adversarial than litigation. They leave obstetricians feeling professionally inadequate, bewildered.

Obstetricians therefore use defensive practice. They either adopt practices to avoid negligence claims, eg caesarean section or they avoid practices to avoid negligence claims, eg breech or forceps deliveries.

Ignorance. These sorts of messages imply very graphically that if a mother attempts a VBAC either:

Some mothers are led to believe that labour is very dangerous; that all these dire consequences will occur without warning with the first contraction.

Caesarean section is major abdominal surgery and as such carries risks. However it is perceived by most people as being safe. What few seem to realise is that VBAC is even safer.

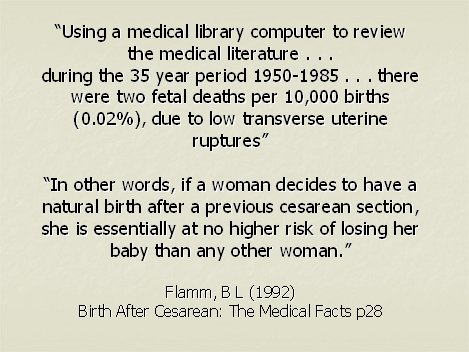

Two reports using computer analysis to compare VBAC against elective repeat caesarean, both came out very strongly in favour of VBAC.

Our own much respected Guide to Effective Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth also supports VBAC and states:

"The likelihood of vaginal birth is not significantly altered by the indication for the first caesarean (including 'cephalopelvic disproportion' and 'failure to progress') nor by a history of more than one previous caesarean."

The ICEA brought out a Review on VBAC in August 1990. This review concludes: For much too long, medical VBAC practices have been based more on opinion rather than on fact. An overview of the VBAC literature from the past half decade reveals: There has been no report of maternal death due to scar rupture during planned VBAC. Reports do document deaths of women due to complications of elective repeat cesarean.

Although the risk of a mother dying through caesarean section is minute, a mother with one or more children at home is likely to view that risk rather differently from a first time mother and she's going to be considering it on a very personal basis. An obstetrician may well only see the mother-and-baby unit before him without perhaps considering her case in the context of the rest of her life situation.

Other, more recent studies have shown a hysterectomy rate that is similar for both elective caesarean and VBAC. It does not appear that elective caesarean lowers the risk of hysterectomy.

In view of the wealth of evidence available supporting the relative safety of VBAC, surely it is fair to conclude that warnings of the dire consequences of VBAC are ill-founded and are no better than emotional blackmail.

Most of the fear centres around two words. Scar rupture. Whereas most people are content to know that the statistics back up their instincts and that VBAC is a reasonable choice, there are some who quite rightly ask.

Statistics are all very well, but if YOU are the ONE it doesn't much matter whether you're the one in ten or the one in ten billion. You are the ONE.

If you are the mother, or the midwife dealing with the mother, who is going to end up as "the one", you too might like to know where your safety margins are going to come from.

Statistics on scar rupture are not available in this country. We don't know how many there are or where they are happening. More importantly, we don't know what's causing them.

In the tragic event of a scar rupture, the general reaction seems to be on of acceptance that - well scars to rupture occasionally don't they? That's the risk you take with VBAC. Well, I want to know why THAT one did, why then, and how - what were the signs, symptoms and circumstances THIS time.

Confidentiality is for the protection of patients. It should not be used to conceal details surrounding scar ruptures. We all need the details to be able to learn from them quantify the risks and keep them in perspective.

Without this information each event of a scar rupture is going to be followed by a spate of impromptu caesareans. Any logical person can look at the evidence currently available and realise nothing can be gained by swopping one set of risks indiscriminately for another!

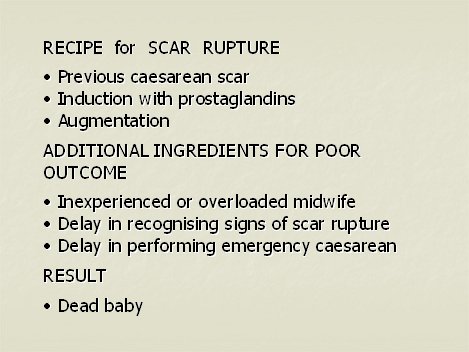

AIMS now have what I call a recipe for scar rupture. There is a list of ingredients, but we don't know how many are optional extras and we don't have quantities. You can't bake a cake without a rough idea at least as to quantities of the ingredients listed.

Until we have the answers to these questions we cannot be sure of making VBAC safer still. Remember, despite the risks it is still relatively safe. But the questions themselves can give a measure of confidence, especially when you bear in mind just how small the risk is.

It is important to keep the risks in perspective. No-one can guarantee us a healthy baby at the end of a straightforward pregnancy and labour. There are risks. We all take risks every day. None of us think of the risks every time we take a car journey for example. Yes we wear our seat belts and we make sure our children are properly strapped in. We take precautions because it is reasonable to do so. VBAC is no different.

Something I often suggest my VBAC mothers do which works for many life situations is to work out exactly what their fears are and where they are coming from. Are they coming from inside or are they really someone else's fears that have been taken on?

When you know what the fear is, research it. Find out enough information to make the fear go away. If it won't go away then listen to it and act on it - take precautions until you are satisfied.

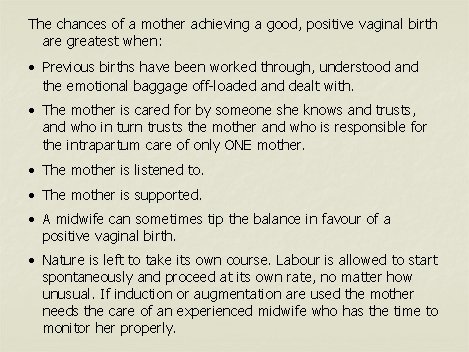

The chances of a good, positive vaginal birth are greatest when:

Caesarean rates are widely accepted as being too high. VBAC mothers hold man of the keys to reducing caesarean rates. They are often clearer about what they want than first time mothers.

Caesarean rates are made up of multiples of "one woman". Everyone in this room has the power to help one woman have a positive vaginal birth. Even if there aren't enough of us here to make a difference to the national statistics we can each of us make a world of difference to one woman. Birth is important.

Enough "one womans" added together will change the statistics.

The first step is to believe that mothers DO NOT put their babies at risk.

The second is to listen carefully to what mothers are trying to say - particularly VBAC mothers.

Thank you for listening to this one.